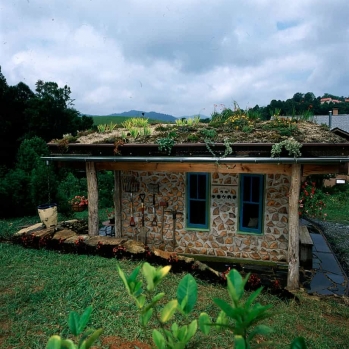

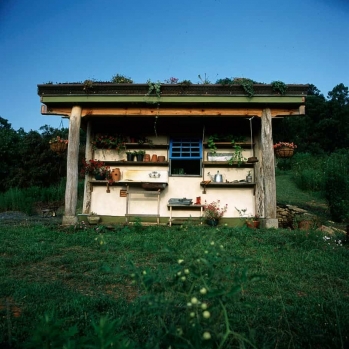

SITE-HARVESTED AND WASTE MATERIALS: “BUILDING GREEN” COTTAGE

There is a movement in the US to rekindle traditional building systems. The concept is that these approaches are less environmentally destructive while creating comfortable, efficient, beautiful spaces. To the extent which this is true, the success of indigenous building systems lies in the fact that they were developed in a specific cultural and climatic context. For example, in hot arid climates with diurnal temperature swings above and below desired interior temperatures, thick earthen walls can act as a form of dynamic insulation to create very comfortable spaces. However, transplant this same system to a wet, cold climate and you essentially have a car without an engine as the passive mechanism which drives the building system isn’t present. The question is can we access the considerable archive of building knowledge represented by indigenous systems and apply them to our contemporary context? This project was conceived to answer that question by applying site-made, local, and recycled materials and passive systems appropriately based on building science principles to create a tiny, flexible, efficient, and beautiful fully functional living space. Different building methods were compared based on performance in relation to a specific microclimate. For example, earthen materials (cob and clay-slip straw) were used on the south face of the building to take advantage of thermal mass to collect solar heat in the winter while straw bales where used on the north face because of their high thermal resistance. The project was conceived as a teaching tool and was designed and built to be documented as a book.